We welcome your feedback and input into this newsletter. In particular, let us know if you would like to know more about a particular topic or if you encounter issues out in the field that need clarification.

You can do this by sending an email to dcvsurvey@amsa.gov.au

Since the last edition

Work on My Boat has continued with a new leisure craft module provided to the developers. VSU also represented AMSA at the ASEAN Regional Forum Workshop on Ferry Safety and the Women in Maritime Breakfast held by the nautical institute SE Australia Branch.

New application forms

As a result of industry feedback, AMSA has recently introduced two new simplified forms to:

- renew a certificate of operation (AMSA 553) where a copy of the existing certificate of operation can be provided; and

- change the certificate (or approval) holder on a vessel permission (AMSA 1780)

The new forms received positive feedback during recent industry user testing noting that the length of the forms and the amount and complexity of information requested on the forms has been reduced.

In this edition

- Mars matters

- Application matters

- New electrical standard now approved

- Trusted processes, accredited people

- What does the term Periodic Survey (in or out of water) mean?

- Transitional vessel stability criteria - boom trawlers

- Welding requirements for vessels built to NSCV C3 using SSC

- Form and content of stability documentation

- How many watertight doors does the NSCV allow?

Mars matters

If you are having trouble accessing MARS or uploading reports - AMSA has a dedicated MARS Support team available to help you. They can be contacted directly via email on MARS.Support@amsa.gov.au. Alternatively, you can call AMSA Connect (1800 627 484) and ask to be put through to a MARS Support team member.

Application matters

Dedicated form for alternate survey process applications

Did you know that AMSA considers alternate survey process proposals?

These proposals may be made where the standard survey process is unreasonable. The power for AMSA to approve an ‘alternate survey process’ is provided by Marine Order 503 and Part 2 of the Surveyor Accreditation Guidance Manual (SAGM).

Until now, these proposals have been submitted on the AMSA miscellaneous form, which has resulted in frequent requests for further information before being able to make a decision. To speed up the processing of these applications and also to provide more guidance to surveyors and industry about the information required to assess these applications we have published a new form (AMSA 1854—Alternate survey process application form). The form is available on the AMSA website and will be able to be submitted by email to dcvsurvey@amsa.gov.au.

New electrical standard now approved

AMSA has completed a comprehensive review of NSCV C5B which has been in place since December 2005. The revised standard (Edition 3) has been approved by the Transport Infrastructure Council and will come into effect on 1 January 2020. The amendments result in contemporary standards for electrical safety on vessels by aligning with the latest Australian Standard (AS/NZS 3004.2).

The principal change to the standard is the requirement for vessels to comply with State or Territory electrical regulator’s requirements. The revised standard also provides:

- Confirmation that protective devices (such as RCDs and RCBOs) are required to be fitted (AS/NZS3004.2) and tested regularly (AS/ NZS3760). Obligations for existing vessels to fit and test circuit protection devices which are also considered to exist in both local WHS/OHS requirements and the National Law General Safety Duties.

- Relevant concurrent requirements of other regulators regarding electrical installations.

- A note stating that there are State and Territory electrical licensing requirements that must be met by persons performing electrical work on low and high voltage electrical systems.

Trusted processes, accredited people

“I cannot imagine any condition which would cause a ship to founder. I cannot conceive of any vital disaster happening to this vessel. Modern shipbuilding has gone beyond that.” Captain Edward Smith, referring to Adriatic

Experts can be wrong; and 5 years later, on the 14th of April 1912, whilst in command of the new vessel the “Titanic”, this statement by Captain Edward Smith was sadly proven to be so.

It raises the question, did Captain Smith’s statement simply sound trustworthy, or was it a legitimate statement arising from a trusted and tested process?

Modern engineering is ever increasing in complexity and requires increased domain experience in order to understand the associated risks. Modern aeronautical, automotive, medical, and yes vessel engineering are all incredibly complicated. It’s true that new technology and advancements have increased safety, but their complicated nature also means that none of us can hope to individually navigate all these questions of vital importance to safety.

Events like the tragedy on Titanic have caused a shift in regulatory practice, away from expert opinion and into trusted processes. Governments and industries have established truth-seeking practices, where independent panels listen to competing claims from multiple experts. They are bound by strict ethical guidelines about how they can be related to the regulated parties as well as including processes for appeal.

AMSA has established trusted systems, which includes processes for:

- Obtaining and maintaining accreditation;

- Conducting and documenting surveys;

- Ongoing inspection and survey of vessels; and

- Processes for appeal.

We administer this system and accredit experts (surveyors) to make recommendations about vessel safety. However, we do not solely rely on trustworthy sounding opinions (recommendations) from our experts, without appropriate supporting evidence.

There are many reasons for this, but essentially it boils down to the fact that there are reasons why people of goodwill may disagree about the technical answer to hard questions that effect safety. In the marine industry the consequences can literally be fatal if we are unable to establish the accuracy, appropriateness, reasoning and standards used to provide a recommendation to support our safety decisions. The potential for catastrophic consequences means that these established processes require evidence and documentation to support the opinions and findings.

So when we ask for documented evidence in support of a recommendation as specified in the Surveyor Accreditation Guidance Manual, Marine Orders, Regulations and National Law, it may be timely to consider whether you would have placed more trust in Captain Edward Smith’s assertion if you knew he had followed a trusted process, such as the SOLAS convention, and had evidentiary material to support his opinion.

What does the term Periodic Survey (in or out of water) mean?

During a periodic survey (whether it be afloat or out of water) an accredited marine surveyor’s role is to conduct the survey in accordance with chapter 4, table 9 in Part 2 of the SAGM.

As mentioned above, AMSA relies on the recommendations of accredited surveyors and recognised organisations when making decisions under the National Law for the issue of certificates and approvals. Because of this, it’s essential that reports and recommendations confirm whether a vessel meets the applicable legislation and standards. Meaning, as far as reasonably practicable during a periodic survey, a surveyor must;

- Detect and assess defects, wear, damage, or variations to the vessel that may affect its ability to comply with the applicable legislation, exemptions and standards;

- Discuss what, if any, repair or rectification work is required in order for these items to comply; and

- Communicate the outcomes of the survey to the person(s) responsible for the maintenance and operation of the vessel including any repair and/or rectification work required.

- Notify AMSA of any corrective actions found during the survey as soon as practicable after becoming aware of the matter—which is a condition of accreditation.

The documentation required to support a surveyor’s recommendation for a periodic survey includes:

- An AMSA 586 survey activity form (as required) - this needs to be sent to AMSA as soon as practicable to notify of any corrective actions; and

- The AMSA 901 recommendation form; and

- Other evidence that support that the survey process is sufficiently covered—such as photographs, third party reports, calculations, lightship verification, inclining reports, previous survey documentation etc.

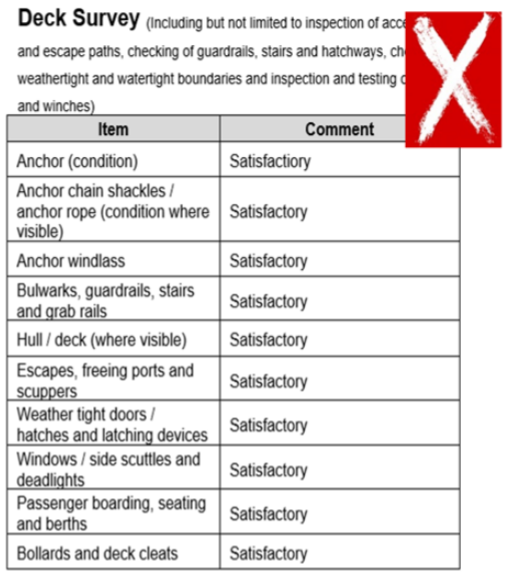

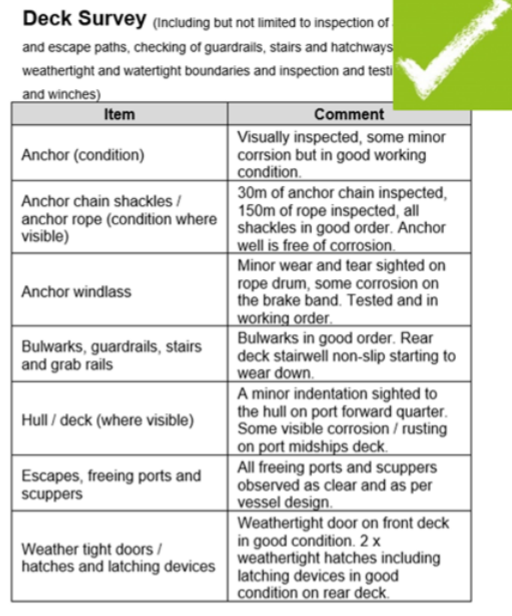

Below are two examples of part of the AMSA 901 form and the provided comments from different attending surveyors.

When populating the AMSA901 a surveyor should avoid using generic terms such as “satisfactory”, “good”, “yes”, “checked” or “ok”, but rather they should document what was actually observed, tested or verified during the survey.

It’s also important that a surveyor references documentation such as original designs, general arrangements or other vessel documentation to ensure that any modifications or alterations have been identified when conducting a periodic survey. These documents should also be submitted to AMSA to support your recommendation(s).

A critical part of the periodic survey process is ensuring that the vessel remains compliant with the applicable legislation and exemptions it was originally designed and constructed for. This may require a surveyor to seek assistance from AMSA or a State marine safety agency to obtain previous vessel history. The AMSA 664 form is available to assist owners, operators or surveyors in locating such documents. The form can be submitted to DCV.Records@amsa.gov.au.

Remember, you can upload all of your supporting evidence including photographs when entering your recommendations in MARS.

Transitional vessel stability criteria - boom trawlers

Under Schedule 2 of Marine Order 503, transitional vessels are required to comply with the requirements of USL Code Section 8C for intact stability. Clause C.5.2.1.1 of section 8C sets out the minimum stability criteria for Category K and L vessels (Class 3 >25m and Class 3 <25m engaged in operations resulting in excessive weights on decks or rigging). Moreover, clause C.5.2.1.4 of section 8C adds that criteria shall be increased as appropriate, to the satisfaction of the authority:

‘A vessel engaged in particular fishing methods, e.g. single or twin boom fishing where additional external forces are imposed on the vessel during fishing operations shall meet the stability criteria of paragraphs (a), (b) and (d) increased as appropriate, to the satisfaction of the authority.’

Prior to AMSA assuming full service delivery for DCVs, state jurisdictions applied the increased criteria for items (a), (b) and (d) individually, if at all. A national criteria is now being applied by AMSA to take into account cod end load and snagged net conditions for vessels to which the USL Code applies can be determined.

For clause C.5.2.1.4, AMSA’s resolution is the stability criteria should be met for the cod end load condition with at least 1 tonne of catch (or actual load if this is in excess of 1 tonne) considered in the cod end. The snagged net condition should consider at least 1 tonne (or actual calculated vertical load if this is in excess of 1 tonne) of downward force acting on the trawl boom at its maximum outreach.

The resulting heeling lever should be plotted on the GZ curve and the resultant heel angle shall be less than 14°.

The weight of the snagged net should be included in the loading table. A note to the master (of the vessel) needs to be included at the beginning of the stability booklet stipulating that great caution shall be taken when attempting to free a snagged net.

This decision takes into account that a limit of between 10 and 14 degrees was applied in USL Code Section 8C as a heeling lever criteria. For example, the criteria for P & Q vessels under clause C.1.3.1.5 was 10°, while the limit under clause C.1.3.4 for category T vessels was 14°.

In addition to this, a result of less than 14 degrees is within the maximum allowable angle of heel permitted in NSCV Part C6A Intact Stability Requirements (section 3.8, Table 4) for a single heeling moment.

Welding requirements for vessels built to NSCV C3 using SSC design rules

We have received a number of enquiries in relation to the welding requirements for vessels designed to SSC rules. Let’s look at how these requirements are set out - NSCV Part C3 Section 5.3.2 describes the requirements for welding by specifying:

5.3.2 Welding

Where the design standard being used does not have its own welding schedule the schedules contained in Annex B shall be used. Then let’s look at what Lloyds SSC say about welding -

Lloyds SSC Part 7, Chapter 2, Section 4, clause 4.3 specifies that the designer must submit a welding schedule:

4.3 Welding schedule

4.3.1 A welding schedule containing not less than the following information is to be submitted: (list of details)

Therefore, if a designer is required to submit a welding schedule, does SSC have its own?

AMSA is of the view that, whilst SSC certainly has welding rules, it is not clear that these rules constitute a schedule. Particularly since clause 4.3 specifies a requirement for the designer to submit a schedule, therefore implying that SSC does not contain its own.

Does this mean you need to head off to NSCV C3, Annex B… The question you need to consider is whether Annex B is suitable for the vessel being constructed?

The mandatory requirements of NSCV C3 are specified in the required outcomes. Therefore, we should consider if the all required outcomes will be met by complying with Annex B for the specific vessel.

Let’s consider an example using NSCV C3, Annex B which does not specify any weld requirement for “stiffener to bottom plate”. A longitudinally framed vessel constructed with no welds connecting the stiffeners to the bottom plate would clearly not meet the required outcomes of NSCV C3.

Generally, for a vessel with scantlings designed to the SSC rules, VSU will accept use of a welding schedule, appropriate to the form of construction being used, based on a recognised standard or drawn from industry best practice, which meets or exceeds the schedule contained in Annex B.

VSU recommends the use of Lloyd’s SSC welding rules and guidance materials in the development of an appropriate welding schedule for vessels over 24m.

Form and content of stability documentation

Stability documentation developed in accordance with the NSCV C6C may be presented in two methods depending on the type of vessel and operations:

- Simplified Stability documentation

- Annex F stability documentation

Under NSCV C6C, clause 5.4.2, both methods require as a basis a stability compliance report that demonstrates compliance with the stability criteria, and an operator’s manual that provides information to the master or those people responsible for maintaining the stability of the vessel.

NSCV C6C, clause 5.4.6.3 permits the use of simplified stability documentation for vessels which meet the following conditions:

- Less than 24m measured length; and

- Class 2 or class 3; and

- 15 persons or less on board (includes passengers, crew and special personnel); and

- Where stability is not required to be periodically checked for compliance against the stability criteria.

Simplified stability documentation must comprise:

- A stability compliance report; and

- An operators stability manual; and

- A stability notice listing vessel specific stability limitations which is posted in the operating compartment.

A stability compliance report must be compiled to document the results of a simplified stability test.

A suggested format for the stability compliance report of a stability test conducted for:

- 7A criteria is outlined in Annex D of NSCV C6C.

- 7B, 7C, 8C, 8D, and 8A criteria is outlined in Annex E of NSCV C6C.

Other formats may be used, however, they must contain at least the information outlined in NSCV C6C Annex D or E where applicable.

Operators Stability Manual

NSCV C6C, clause 5.4.6.3(b) contains a note indicating that templates for operator stability manuals are available for download from the NMSC website. AMSA recognises that this is no longer available and that no substitute has been provided. NSCV C6C, Annex F, clause F.8 may be used as a guide to determine the applicable information to meet the requirements of clause 5.4.6.3 (b).

Stability notice

A stability notice is mandatory if the simplified stability option is chosen. Annex J of NSCV C6C provides guidance as to the content of a stability notice, however, in general terms it must provide information to the master about stability limitations of the vessel in its intended operations. It may include maximum passenger numbers and their distribution; limiting deadweight, windage area and VCG of deck cargo; limiting lift mass height and radii of cranes/davits; sail configuration with respect to wind speed; securing of cargo and equipment; and general warnings about good vessel handling practices.

Annex F Stability

Where a vessel does not qualify for simplified stability or the surveyor has chosen not to implement it, its stability documentation must comply with the form and content outlined in NSCV C6C Annex F. It is important to note that this Annex is a mandatory part of the standard and must be complied with in its entirety.

AMSA will request that a stability submission be revised if the form and content of a stability book is not in accordance with Annex F, and this may delay the processing of an application for a Certificate of Survey.

In accordance with Clause F4, the requirement to provide a stability compliance report and an operator’s stability manual is deemed to be met if the requirements of Annex F are complied with.

Where the operator is required to periodically check the compliance with the stability criteria (see examples below) and the vessel is of a length specified in table 3 of NSCV C6C, an additional section showing worked examples of how to carry out a stability assessment must be included in the stability book as outlined in Table F1 of Annex F.

Examples of vessels that require periodic checking of stability:

- Vessels carrying a cargo mass that is within allowable limits but that may not meet the criteria if it is loaded incorrectly e.g. landing craft, bulk cargo vessels, large fishing vessels;

- Vessels engaged in lifting and/or counter-ballasting and/or cargo loading where it compliance may not be sufficiently represented in a maximum load/height/reach diagram as part of a notice to the master. E.g. large crane barges with deck cargo and fixed/water ballast.

How many watertight doors does the NSCV allow?

The NSCV is in areas a particularly complex and encompassing set of standards, which to review in full for every vessel would be a very significant undertaking. As such, it is common practice to skim through many sections and refer straight to a table, formula or particular prescriptive requirement. This practice (although fine in most cases) does create possibilities where requirements or areas of application to be missed or misapplied.

The quantity of watertight doors allowed in a vessel is a pertinent example of the above. Chapter 9.3.8 Specific requirements for watertight boundaries of NSCV Part C6B, and particularly Table 38 – Applicable Types of watertight doors (see below) has been a source of disagreement and limitation for many years. Even so far as the marine state agencies attempting to conduct both a standards amendment and to propose a Generic Equivalent Solution, neither of which were successful.

| Type 1:sliding door, operated by power and by manual gear | Type 2: sliding door, operated by manual gear only | Type 3: hinged door | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additional limits on application | None | Door sill not more than 4m below the bulkhead or freeboard deck | Door sill not more that 2.5m below the bulkhead or freeboard deck. Maximum width 800mm | |

| Flooding risk category | I | Required where type 2 or type 3 cannot apply | Optional for vessels having no more than four watertight doors per hull (1) | Optional for vessels having one or two watertight doors per hull (1) (2) |

| II | Required where type 2 or type 3 cannot apply | Optional for vessels having no more than four watertight doors per hull (1) | Optional for vessels having one or two watertight doors per hull (1) (2) | |

| III | Required where type 2 or type 3 cannot apply | Optional for vessels having no more than three watertight doors per hull (1) | Optional for vessels having a single watertight doors per hull (1) (2) | |

| IV | Required where type 2 cannot apply | Optional for vessels having a single watertight door per hull (1) | Not applicable | |

In general the above table is referred to directly for all vessels when determining the damage requirements for a vessel, and due to the particular wording for a vessel that has in excess of the minimum allowed number of WT doors, the requirements become extremely difficult to pass.

Example:

Applying the table directly – A flooding risk category III vessel with three hinged WT doors per hull (one more than specified) would require that the vessel meet the Chapter 8.4 Comprehensive stability and buoyancy in the equilibrium flooded condition with all three doors assumed open (i.e. the Steering room, Engine room, Accommodation void and Void 1 all assumed flooded).

However this is not always correct, and often Table 38 is being applied incorrectly to vessels. Paraphrasing Chapter 9.2 Application – the chapter only applies to boundaries necessary to pass damage stability.

For instance, if the above vessel passed damage stability without the aft engine room WT bulkhead, then that bulkhead and subsequent WT door do not count to the number of WT doors considered by Table 38. However as designers and surveyors you must prove this before surpassing the numbers specified in the Table.

9.2 Application

The provisions of this chapter shall apply to all watertight boundaries that are assumed to be watertight for the purpose of compliance with this Subsection.

NOTE: Boundaries that are not essential to compliance are not subject to these provisions. Typically a boundary is not essential when the vessel meets a higher standard than the minimum specified in this Subsection or the boundary cannot be counted as effective for other reasons such as the minimum extent of damage provisions.

None of us know (or can remember) everything, it’s important you read the entire chapter in detail from time to time.